Making Meaning in a Course that Students Dread

I'll never forget the moment when I realized that some of my students hadn’t really understood much of anything in my chemistry class. Students had just completed an open-ended experiential lab-based project at the end of the course, and I decided to interview each student to see what they had learned from the project and the course. When talking with one group, my spirit was crushed. I asked them some rudimentary questions about what we had learned throughout the year, and they didn’t have a clue. It was as if they hadn’t been in the class all year. I felt dejected and didn’t know what to do.

What had no doubt happened was that these students had studied just enough to pass each test by regurgitating facts—but deep down, they didn’t understand the main principles of chemistry. Upon reflection and with an honest look, I realized that their lack of making any meaning from the course was my fault. I had focused on getting students to pass the tests and demonstrate their knowledge—but little work had been done to get them to truly understand the big ideas of chemistry.

Our system of lecture, practice, test, and repeat didn’t foster deeper understanding. This, among other things, was one of the key reasons I began to rethink school. It began a journey from a traditional teacher to flipped classroom teacher and then to a mastery learning teacher. Along the way, I learned better how to help students construct a deeper understanding of what they were learning.

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang (Lahey, 2015) posits that students learn best when they are emotionally invested in the topic. But I teach a required course (Chemistry), and many students aren’t overtly interested in the intricacies of the atom or the wonder of electrons. Most students, upon entry into my class, only think about explosions and dangerous chemicals. So part of my job is to get them to care about the course, why it is important to understand, and truly engage in their learning.

As I see it, helping students become meaning-makers takes a multi-faceted approach. Below are a few things that I have done that have helped students make meaningful connections to chemistry.

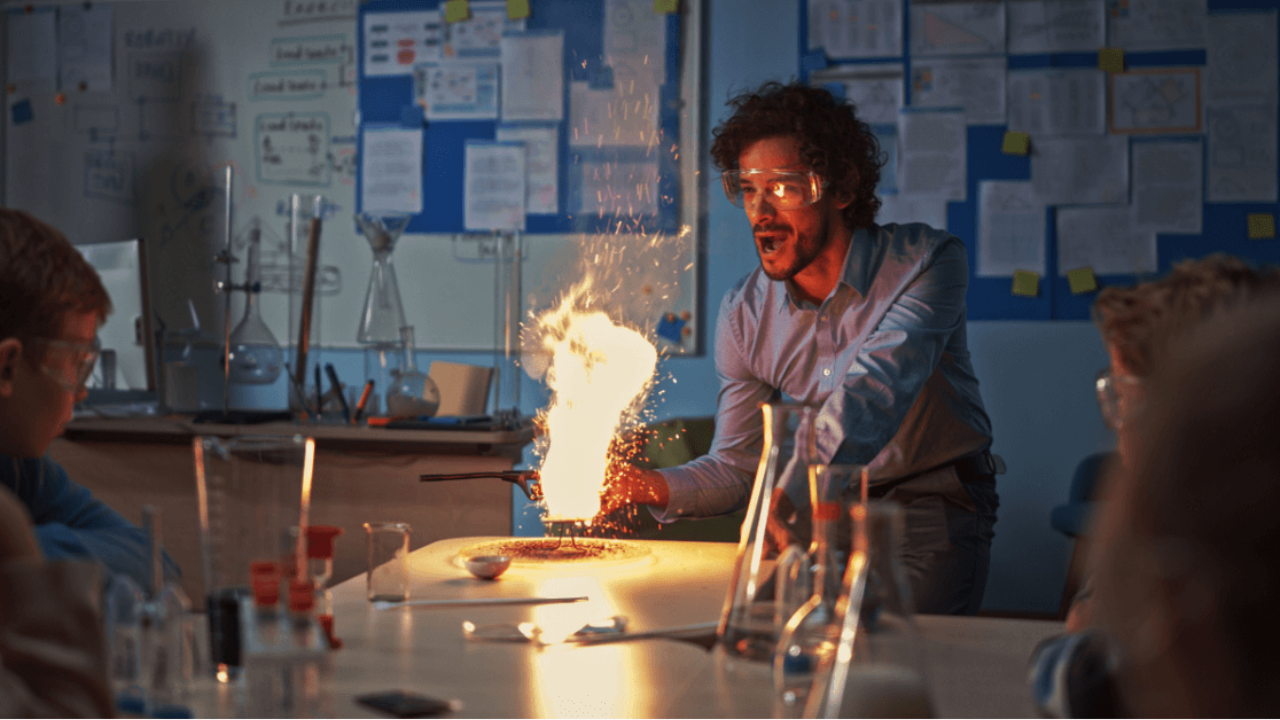

Start the Year Out with a Bang: I have started my chemistry class the same way for over 25 years. On the very first day, I don’t go over the syllabus (boring)—instead, I bring a clear liquid to the class that I tell them was found at a crime scene. We need to determine what it is in case it has something to do with the crime. I ask them to tell me how they might identify the liquid—not what it is—yet! I jot down on the board all of their ideas. They say things like, check the pH and temperature, find its boiling point, test if it lights on fire, drink it, smell it, etc. I dutifully write all of these down. I also bring several things that would quickly test the liquid. I let one student smell it (following appropriate safety protocols) and usually test the pH. I then pull out what I call the “Flammability Tester.” This is simply a candle in an evaporating dish. I then light the candle pour, out the liquid, and then wala—it catches on fire. And…drum roll please…right before the bell rings, I drink down the whole bottle.

I then say welcome to Chemistry. Of course, they all want to know what I drank on the first day—and I tell them that I will only tell them all will be revealed when they graduate from high school (most of them are in the tenth grade). And then every year at graduation—they mob me and ask—and I finally tell them. This simple activity generates a buzz. Some students do research over the year and give me all kinds of ideas about what they think I drank on the first day. And my response is always the same—wait until you graduate. FYI—if you are a chemistry teacher and want to know the liquid—email me and I will fill you in.

Intrigue Them

When students evaluate my class every year, they especially enjoy the chance to experience science. This goes beyond your typical laboratory experiences. I teach them how to light each other on fire safely. I have them do lots of mini-experiments. I have a series of take-home experiments where they do them for their parents and have to explain what happened and why it happened. I also do a variety of teacher-led demonstrations when it isn’t feasible (or safe) for them to do it on their own.

Give them Ownership

I have written extensively on Mastery Learning with a Flipped Learning Twist, and I can’t say this enough. When I stopped lecturing, and let students move through the content at flexible paces, it was the biggest game changer in my professional career. Students so appreciate Mastery Learning for a variety of reasons. They love that they can retake a test. All “tests” are simply learning experiences. They also love when I give them choice and voice in how they demonstrate mastery. If you want to learn more about Mastery Learning, I encourage you to simply go to my website and sign up for the newsletter and/or get my latest book, The Mastery Learning Handbook.

Genuinely Care About Your Students: Students don’t care what you know until they know you care…about them. I have found that students who know you are there for them will do anything for you. They will even talk about a required course that they were dreading. Even Chemistry! So find ways to show that you care. Here are a few things I do.

- Learn their names fast. I have a system where I learn their names before they walk in the door. So on the first day, I am pretty sure that I know 90% of their names. See my post on how I do this.

- Have them tell you about themselves. Instead of me going over the boring syllabus, I have them watch three short videos about the class. One discusses how and why they will learn via mastery, the second one is a video from last year’s class giving them advice, and the third is where I introduce myself to them. Then in return, I have them make a 2-minute video where they introduce themselves to me. I then watch every video, write their words down in a Google Doc, and then print it out. Because I teach via mastery and I don’t do big class presentations/lectures, I try and chat with a few students over the next few days and ask them about their interests. Then as the year progresses, I try to connect what I know about their lives to my required content. One of my students was a star basketball player. And when I explained to her some of the Chemistry in basketball terms—boom! She got it. FYI—I have made a copy (without names) of one of my sheets for you to look at.

- Questions of the day. I start out each class with an icebreaker question. I also use this to take attendance. Each student answers the question and it usually has nothing to do with science. Sometimes the questions are silly—What was the worst fashion choice you ever made?—and sometimes they are more serious—What is something important a grandparent or older mentor taught you? If you want to see my list of questions, they are here. Note—I just Googled icebreaker questions and got a lot from Kaitie Bergmann (my daughter and a high school English/Drama teacher).

- Actually Care. All the strategies in the world will never replace you actually caring. Students can detect someone just trying to care from a mile away.

Frankly—it isn’t rocket science. You are already passionate about what you teach (at least, I hope you are). Be enthusiastic about your field. Then find hooks into the lives of your students, give them ownership (this is the hardest to do), and lastly, actually care!

——————

Lahey, Jessica. “To Help Students Learn, Engage the Emotions.” The New York Times, 4 May 2016.